Technical Summary

From tin halide perovskites serving as light-absorbing layers to tin oxides and sulfides functioning as charge transport layers, tin’s versatility is shaping new solar architectures. Its use extends beyond the active layer, contributing to transparent conductive oxides and forming the soldered interconnects in solar ribbons.

Researchers worldwide are investigating ways to overcome current limitations in tin-based active materials such as oxidation instability and energy level misalignment, with promising strategies already enhancing device performance and longevity. This page provides a technical overview of how tin is being applied in solar cell technology, the challenges being addressed, and where innovation is likely to take the field next.

Please use the Feedback buttons to contact the Tin Valley team with your comments, corrections, or updates.

Introduction

Solar cells are essential for the clean energy transition as they provide a sustainable, renewable source of electricity by harnessing the sun’s abundant energy. With growing research in this area, advancements in efficiency, cost reduction, and material innovation are accelerating their adoption, helping to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and foster a more resilient energy system.

Solar cells are essential for the clean energy transition as they provide a sustainable, renewable source of electricity by harnessing the sun’s abundant energy. With growing research in this area, advancements in efficiency, cost reduction, and material innovation are accelerating their adoption, helping to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and foster a more resilient energy system.

Active tin materials are under extensive global development, particularly for developing more sustainable and cost-effective photovoltaic (PV) technologies. They are being explored in various types of solar cells, including tin-based perovskites and as thin-film light absorbers.

Tin also has other uses, such as being a component of the electron transport layer inside solar cells, and in the solar ribbon used to connect the solar cells together.

Tin-based solar cells aim to reduce the environmental impact by replacing toxic or scarce materials like lead, cadmium, and indium, offering a greener alternative for large-scale solar power generation.

Operating principles

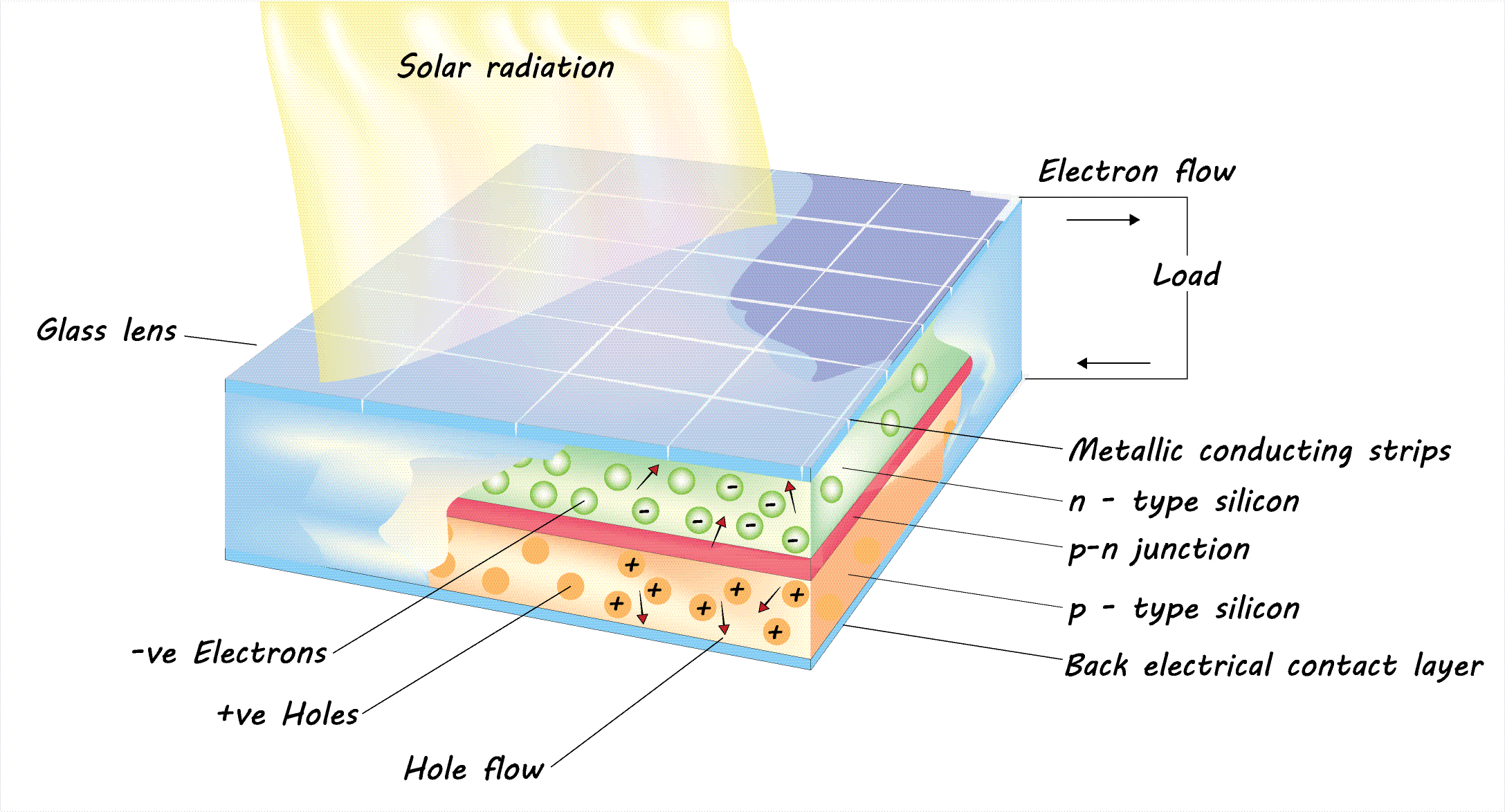

When a light absorbing element absorbs sunlight (photons) inside a solar cell, it excites said elements electrons, causing them to move to higher energy states.

When a light absorbing element absorbs sunlight (photons) inside a solar cell, it excites said elements electrons, causing them to move to higher energy states.

This excitation generates electron-hole pairs where the hole represents a missing electron, and acts as a positive charge.

Inside the solar cell also is a P-N junction (positive-negative) which separates the generated negative electrons from the positive holes. This is essential to ensure that charge carriers (electrons & holes) cannot recombine before being extracted.

The P-N junction is made up of a P-type semiconductor that has an abundance of holes (positive), and an N-type semiconductor that has an abundance of electrons (negative). Both of these semiconducting materials are usually made of silicon doped with other elements to create excess holes/electrons in traditional silicon solar cells.

The P-N junction creates an electric field that pushes the generated electrons towards the N-type layer and the holes towards the P-type layer, separating the two. The transfer of electrons from the light-absorbing layer to the N-type electrode is facilitated by the electron transport layer (ETL) which is often made of tin oxide. The transfer of holes is facilitated by the hole transport layer (HTL).

Electron-selective contacts (ESCs) and hole-selective contacts (HSCs) are crucial components in solar cells that improve charge extraction efficiency. ESCs facilitate the movement of electrons from the electron transport layer (ETL) to the n-type electrode, while HSCs enable the efficient transport of holes from the hole transport layer (HTL) to the p-type electrode, both preventing charge recombination. By selectively allowing only electrons or holes to pass through, these contacts enhance the overall power conversion efficiency and stability of solar cells.

The electrons are collected by an electrode (usually made from ITO or FTO) on the front, N-type side, and the holes on an electrode (usually made from Au or Ag) on the back, P-type side. This forms an electric current when the circuit is complete.

Tin in solar cells

Silicon solar cells have been the traditional choice in the past but researchers are looking into new technologies to improve cost, manufacturing flexibility, efficiency improvements, and sustainability.

Silicon solar cells have been the traditional choice in the past but researchers are looking into new technologies to improve cost, manufacturing flexibility, efficiency improvements, and sustainability.

Silicon solar cells typically produce higher efficiencies than competing technologies as they are more advanced, with a higher technology readiness score.

Silicon-based solar cells are also being combined with other solar technologies to form tandem solar cells. These cells are able to absorb more types of sunlight due to the combination of the different light absorbing materials, resulting in higher efficiencies.

The highest recorded (commercially available) solar cell is a tandem solar cell which combines perovskite and silicon cells to reach an efficiency of 28.6%. This cell is being produced by Hanwha Qcells.

Tin in solar ribbon

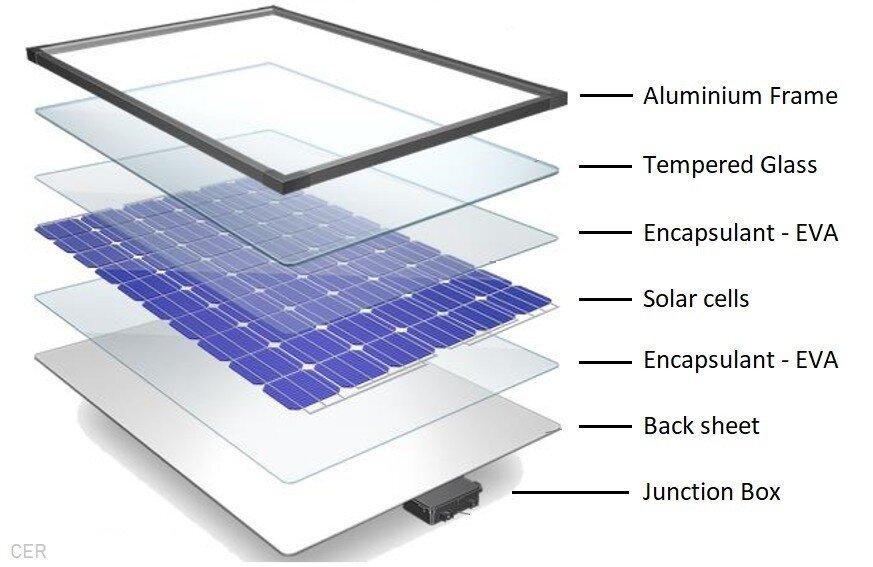

Tin is used in the solar ribbon used to connect solar cells together, forming a solar panel. Solar ribbon is a conductive metal strip essential for creating electrical pathways that carry generated current from individual solar cells. Solar ribbon is often made from copper dipped and coated in tin-based solder.

Tin provides a protective barrier for the solar ribbon, especially since solar panels are exposed to harsh environmental conditions. Tin also enables flexible and thin interconnects, which is essential for lightweight solar panel designs.

Tin-lead & pure tin perovskites

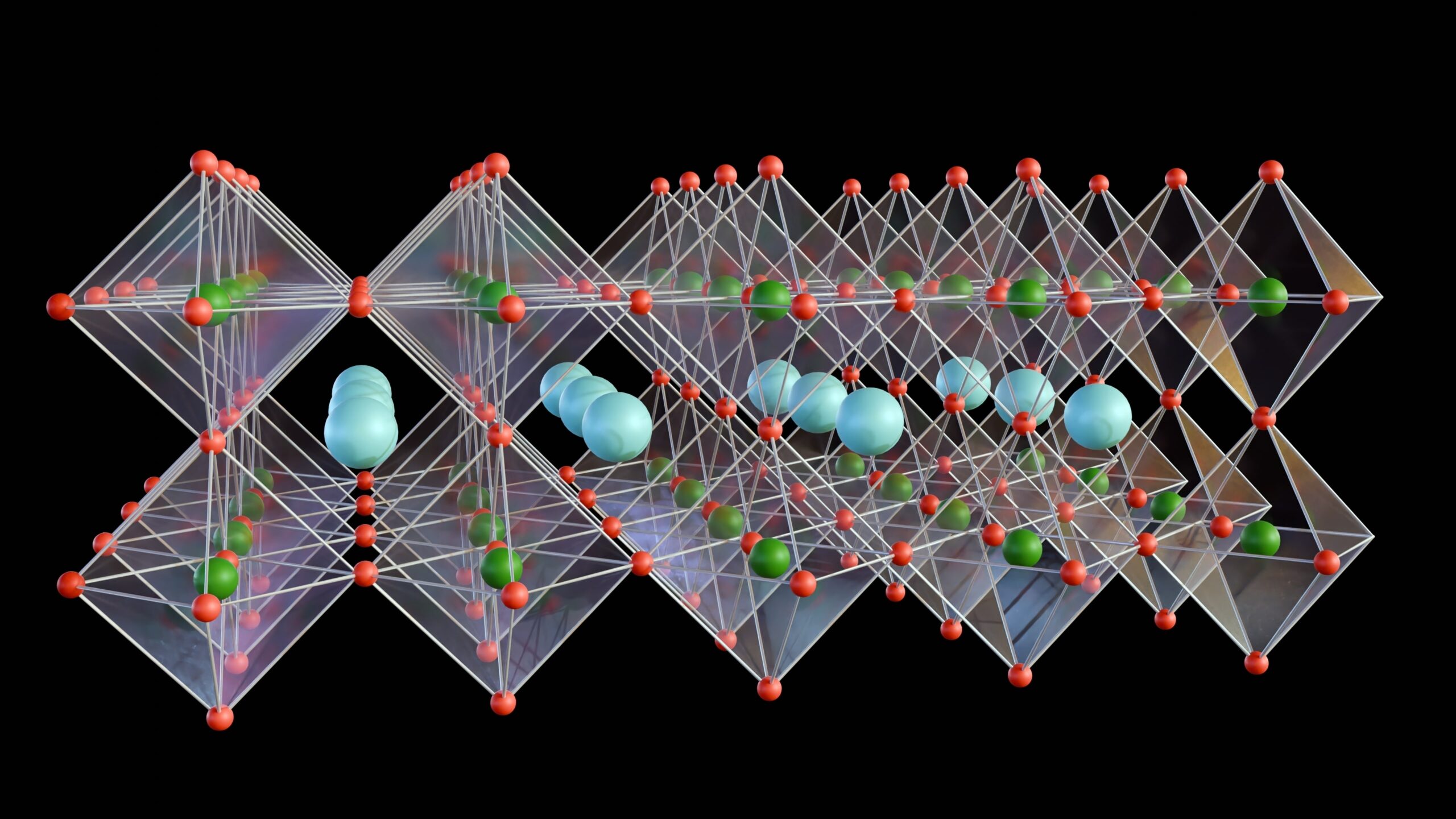

Perovskite solar cells are a type of photovoltaic technology that uses perovskite-structured materials as the light-absorbing layer. They work via the same mechanism as all solar cells.

Perovskite solar cells are a type of photovoltaic technology that uses perovskite-structured materials as the light-absorbing layer. They work via the same mechanism as all solar cells.

Perovskite structures have the general formula of ABX3, where A is an organic cation, B is a metal cation, and X is a halide. Traditionally Pb(II) is used as the B cation, but due to toxicity concerns, a replacement is required.

Sn (II) is an ideal candidate for the B cation due to its ability to absorb light in the visible spectrum and convert it efficiently to charge carriers. Some examples include methylammonium tin bromide or iodide (MASnBr3 or MASnI3).

Pure tin-based perovskites rather than tin-lead perovskites offer a more environmentally conscious alternative, due to the removal of lead.

Lead-based perovskites are rapidly approaching efficiency records set for silicon based solar cells, with an increase in perovskite efficiency of over 23% since 2009.1 A new efficiency record for lead perovskites was set by UNSW and Soochow University at 27%.2

Benefits

There are benefits to using tin perovskite solar cells in comparison to other solar technologies. To begin with they are non-toxic and more environmentally forward as they do not contain lead. Additionally, conversely to lead, tin-based perovskites break down in air to non-toxic compounds. This makes tin perovskites suitable for more niche applications also, such as wearable electronics.

Tin halide perovskites also posses a narrower band gap which is close to the theoretical limit for solar energy conversion (1.2-1.4eV). This means that it can absorb a different part of the solar spectrum that other materials cannot, meaning more of the solar spectrum can be utilised. Additionally, the bandgap is tuneable, allowing for optimisation for different applications.

Tin-based perovskite semiconductor materials have a small exciton binding energy of only 55 meV. Exciton binding energy is the electrostatic attraction between the electron-hole pairs forming what is called an exciton. Therefore a low exciton binding energy means that it is easier to separate the electron and hole, which is essential for the functionality of a solar cell.

Tin-based perovskites are also noted for their high carrier mobility. This is a measure of how quickly the generated holes and electrons can move to the ELT and HTL. Faster movements means a lower likelihood of charge recombination, which would reduce efficiency.

An advantage of perovskite type solar cells is a lower-cost and simpler fabrication process. This is due to the fact that the perovskite absorber layer usually can be dissolved in common organic solvents and deposited as thin films using spin coating, dip coating, and spray coating techniques. In contrast, silicon solar cells require higher temperatures and more complex synthesis.

Tin-based perovskites are also being explored for flexible solar cells.

Issues

There are issues to overcome however to ensure that tin-based perovskites can continue to compete with alternative solar cell efficiencies. To begin with, tin-based perovskites suffer from inherent instability. This is due to favourability of Sn2+ to oxidise to Sn4+. This leads to the formation of vacancies as further electrons are lost from the tin ion, turning the material into a p-type material (increase in the number of holes). This leads to a surge in charge carrier recombination, severely reducing efficiency. The oxidation of Sn2+ to Sn4+ can also be accelerated by the formation of superoxide, which is formed by the reaction between photo-excited electrons and oxygen molecules.

Additionally a lower power conversion efficiency (PCE) is observed in tin-based perovskites. One reason for this is the higher level of non-radiative recombination. This is where generated holes and electrons recombine without emitting a photon, so energy is lost. The difference in the nature of the defects or sites that facilitate recombination leads to varying recombination rates. The oxidation of Sn2+ can also lead to the formation of vacancy defects, such as halide vacancies (depending on material), which can lower efficiency.

Pure tin-based perovskites can also face challenges with energy level misalignment when interfaced with the hole transport layer (HTL). This means that the perovskites valance band and the HTLs energy levels are not aligned, which is essential for efficient hole extraction and a reduction in charge recombination. Therefore this can decrease the efficiency of the cell.

During synthesis, tin perovskites suffer from rapid crystallisation, which can lead to poor film quality, high defect density and poor overall performance.

Resolutions

Researchers have been exploring ways to resolve issues with tin-based perovskites. One way to help resolve the issue of tin oxidation is to add molecules that can inhibit said oxidation. In literature, the addition of thiolactic acid (TA) has been explored. TA contains carbonyl (C=O) and carbon sulphur (C-S) functional groups. These groups are able to interact with Sn2+ which inhibits the oxidation reaction.3 The addition of TA also improves the morphology of the overlying perovskite film, leading to fewer defects and improved overall PCE.3

Additionally, additive reducing agents such as GeI2 can be added into the perovskite precursor to suppress Sn2+ oxidation similarly to the addition of TA. GeI2 also acts as a crystallisation regulator helping to control the fast crystallisation kinetics of tin perovskites.4

Carefully regulating the tin additive concentrations can also help manage the formation of vacancies or defects that can influence tin oxidation.

Another example is engineering the perovskite material itself. For example adding DMA (dimethylammonium) cations can be found to optimise the energy-level alignment with the HTL, reducing the hole-transport barrier.5

Tin in thin-film solar cells (CZST)

Beyond perovskites, tin also plays a crucial role in thin-film chalcogenide solar cells, particularly in Cu₂ZnSnS₄ (CZTS) and its selenium-alloyed variant Cu₂ZnSn(S,Se)₄ (CZTSSe), collectively referred to as CZST or kesterite absorbers. These materials are designed as sustainable alternatives to CIGS (Cu(In,Ga)Se₂), replacing scarce or toxic elements like indium and gallium with abundant, non-toxic tin and zinc.

In kesterite solar cells, Sn⁴⁺ acts as a key cation balancing the lattice structure and directly influences the electronic band gap (1.0–1.6 eV) and carrier transport properties. The oxidation state and coordination of tin play a major role in determining defect formation, carrier concentration, and band alignment, all of which are critical for high photovoltaic performance.

While kesterite solar cells have achieved lab efficiencies of up to ~13.8%, their commercial deployment remains limited due to challenges such as tin-related secondary phase formation (e.g., SnS, SnSe) and cation disorder affecting charge transport. Ongoing research is addressing these issues through composition tuning, alkali doping, and improved annealing atmospheres to stabilize Sn⁴⁺ and enhance crystal quality.

Nevertheless, the abundance, non-toxicity, and potential scalability of tin make CZST thin films an important avenue for next-generation, environmentally sustainable solar technology.

Tin as an ETL material

Tin has another use in solar cells as an electron transport layer (ETL). The role of the ETL is to collect electrons generated in the light-absorbing layer and transport them to the electrode whilst blocking the holes generated from passing through.

Tin (IV) oxide (SnO2) is the ideal candidate as it has excellent electron mobility and is transparent to visible light, allowing sunlight to reach the light-absorbing material. It also has a wide band gap of 3.6 eV (at 300K)6 which reduces the recombination of charges, improves the energy level alignment between the ETL and the absorber material, and improves material stability. Tin (IV) oxide as an ETL has exhibited excellent performance with halide perovskites.6 Other benefits include tin oxide being a cost-effective and abundant material.

In recent literature, modifications to the tin oxide ETL have been trialled to further enhance the overall cell efficiency. One paper used (111) facet-engineering cubic phase tin oxide (C-SnO2).7 The C-SnO2 provides a large surface contact area with the perovskite absorber layer, enhancing charge transfer and electron extraction efficiency.7

Other examples include incorporating 2D SnPS3 nanosheets into the SnO2 ETL. The S atoms help to fill oxygen vacancies in SnO2.8 This reduces the number of defects in the material, improves the energy level alignment and electrical conductivity, as well as improving overall efficiency from 21.51 to 23.01%.8

Tin as a HTL material

Tin is also used in the hole transport layer (HTL), although less frequently. The role of the HTL is to collect holes generated in the light-absorbing layer and transport them to the relative electrode whilst blocking the generated electrons from passing through.

Tin (II) sulphide can be used as the HTL material in perovskite solar cells. SnS is a cost-effective, abundant, non-toxic material, with the added benefit that it has direct-bandgap energy.9 This means that electrons can transition between the valence and conduction band without needing to change momentum, allowing for efficient light absorption and emission. SnS is a favourable HTL when paired with MASnI3 absorber material in perovskite solar cells.

Cadmium zinc tin selenide (CZTSe), copper iron tin sulphide (CFTS), and copper zinc tin selenide sulphide (CZTSSe) have also been examined as inorganic HTLs for quantum dot-sensitised solar cells. These HTL materials can have advantages over organic HTLs, such as improved band alignment, stability, and transparency.10 CZTSSe exhibited the highest performance of these examples with a PCE of 22.61%.10

Tin in the transparent conduction electrode/oxide material (TCE/TCO)

The transparent conduction electrode (TCE) is positioned at the front of the solar panel acting as the front electrode. The TCE has two main functions; to allow sunlight to pass through to the light absorbing layer, and to conduct electricity by collecting the electrons generated from light absorption. This means TCE materials need to be transparent and to have good electrical conductivity.

Indium tin oxide (ITO) is a common candidate for the TCE. ITO contains around 10% tin oxide.11 ITO dominates as a TCE material in silicon heterojunction (SHJ) solar cells, but it also used in perovskite solar cells.11 ITO is an ideal material for the TCE as it has excellent optical transmittance (near 90% in the visible region), low resistivity (10⁻⁴ Ω cm) indicating high electrical conductivity, and exceptional corrosion resistance.11

Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) is also used as a TCE material. It has similar properties to ITO but avoids to use of more scarce and expensive indium. It is important to note that FTO is slightly less transparent and conductive then ITO, but FTO is more chemically and thermally stable.

ITO and FTO are both brittle materials which can limit solar cell flexibility.

Perovskite performance

Click to expand

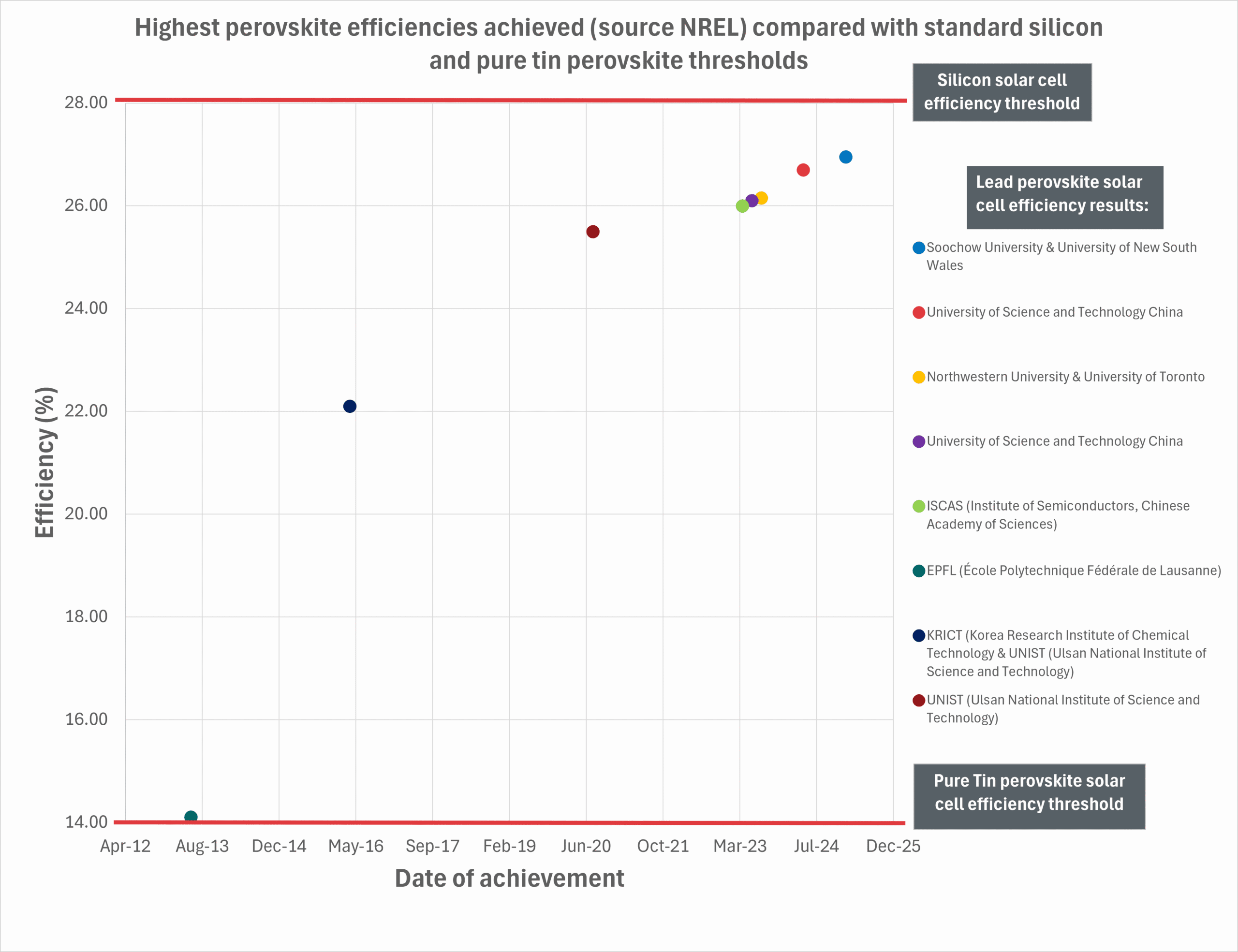

Recent data from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) demonstrates a clear and impressive upward trend in the efficiency of lead perovskite solar cells, with several leading research institutions achieving performance levels that rival conventional silicon photovoltaics. Between early 2023 and early 2025, lead-based perovskite solar cell efficiencies have climbed steadily from around 26.0% to almost 27%, with the most recent result—achieved by Soochow University and the University of New South Wales—falling just short of the ~27.6% benchmark typically associated with high-efficiency silicon solar cells. This trajectory highlights the remarkable pace at which lead perovskite technology is advancing and the hope for a similar trend with tin-lead and pure tin perovskite performance.

The graph captures breakthrough results from eight institutions, including repeated entries from the University of Science and Technology China and Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, reflecting sustained progress in their research. Other high-performing collaborations include Northwestern University with the University of Toronto, and ISCAS (Institute of Semiconductors, Chinese Academy of Sciences). Notably, many of these leading efforts are concentrated in China, underscoring the country’s deep investment and leadership in perovskite solar innovation. The consistency and magnitude of efficiency improvements suggest that further records may be imminent as researchers refine device architectures and materials.

In addition to showcasing the leading edge of perovskite performance, the chart includes a lower threshold line at around 16.6%, representing the highest efficiency currently achieved for pure tin-based perovskite solar cells. While this is significantly lower than the lead-based counterparts, it actually reflects a major leap forward for tin-based technologies—long seen as the most promising non-toxic alternative. Tin perovskites are a much younger technology, still overcoming challenges related to oxidation, film formation, and stability. Nevertheless, their efficiency has improved markedly in recent years, and this progress is all the more encouraging considering the comparatively short timeframe of development. The fact that tin-based devices have already reached efficiencies above 16% is a strong indicator of their potential, especially as global efforts intensify to replace lead in photovoltaics.

In summary, the graph not only highlights the accelerating maturity of lead-based perovskite solar cells—now on par with silicon—but also draws attention to the emerging promise of pure tin perovskites. Although still in an earlier stage of development, tin-based systems offer a safer and more environmentally sustainable pathway forward. Continued research into stabilising and optimising these materials could pave the way for truly green, high-efficiency perovskite photovoltaics.

Estimated tin usage in solar cells

On an industrial scale today, global PV is likely consuming almost 60 thousand tonnes of tin per year as a solder in solar ribbon. Growth will slow due to thrifting but may reach 70 thousand tonnes by 2035. Tin use in perovskite active materials and electron transport layers is on much smaller scale based on thin film technologies, likely totaling tens or hundreds of tonnes at present.

The multiple uses of tin in solar technologies is an important demonstration of the crucial role of tin in making the future.

Manufacturing solar materials

Spin-coating

Spin-coating is the most widely used method in laboratory-scale fabrication of perovskite materials. A small volume of precursor solution is deposited onto a substrate, which is then rotated at high speed to spread the solution evenly through centrifugal force. This technique produces uniform, smooth films with controllable thickness, which is crucial for achieving efficient charge transport and minimal surface defects.

Spin-coating is especially suitable for tin halide perovskites due to their solution processability, but rapid crystallization of Sn²⁺ compounds requires careful optimization of spin speed, time, and antisolvent dripping to prevent poor film quality and pinholes.

Dip-coating

Dip-coating involves submerging and slowly withdrawing a substrate from a precursor solution, allowing a thin film to form through solvent evaporation. It is more amenable to roll-to-roll scalable manufacturing, making it attractive for industrialisation of tin-based perovskite solar cells.

The method is simple and cost-effective, but film uniformity can be influenced by withdrawal speed, solution viscosity, and ambient humidity, which must be tightly controlled for reproducibility.

Blade-coating

Blade coating uses a mechanical blade to spread a liquid precursor across a substrate at a controlled gap and speed. It is ideal for creating large-area perovskite films for scalable module fabrication and is increasingly used for tin halide absorber layers.

Compared to spin-coating, blade coating is more material-efficient and compatible with high-throughput processing, making it a strong candidate for commercial tin perovskite production.

Inkjet & spray-coating

These techniques are digital, maskless printing methods onto flexible or irregular surfaces. Inkjet printing delivers droplets of precursor solution with precise spatial control, enabling customised architectures such as interdigitated electrodes or graded layers.

Spray coating uses atomized mist to deposit precursor films over large areas and is especially attractive for low-temperature fabrication of SnO₂ ETLs. Both methods are promising for flexible electronics, wearable PV, and tandem cells, but challenges remain in controlling film uniformity and avoiding clogging or overspray.

Vapor deposition

Vapor deposition methods are used to create high-purity, highly crystalline perovskite films, although they are less common for tin-based materials due to Sn²⁺ volatility and reactivity. However, dual-source vapor deposition or chemical vapor deposition (CVD) can be used for SnI₂ and organic cation co-deposition to form tin perovskite layers with enhanced crystallinity and reduced pinhole density.

For SnO₂ ETLs, atomic layer deposition (ALD) and sputtering have been explored, especially in tandem devices requiring ultrathin, defect-free films. These methods offer excellent film control but are expensive and less scalable than solution-based processes.

Competing solar technologies

Crystalline silicon

Crystalline silicon is the most dominant solar cell technology, accounting for a large percentage of global PV production. It offers high efficiency, proven long-term stability, and well-established supply chains.

While silicon excels in durability and efficiency, it is energy-intensive to manufacture and typically rigid, making it unsuitable for lightweight or flexible applications. Tin-based perovskites, by contrast, are solution-processable, flexible, and potentially cheaper, though they lag behind in efficiency and lifespan. Tin perovskites are unlikely to replace c-Si but may complement it in tandem structures or flexible devices.

Lead-based perovskites

Lead halide perovskite solar cells have shown exceptional performance, achieving high efficiencies. They share many processing advantages with tin perovskites, including low-cost fabrication and tuneable bandgaps.

Lead perovskites outperform tin perovskites in terms of efficiency, stability, and maturity. However, toxicity concerns surrounding lead have driven efforts to find safer alternatives. Tin-based perovskites offer a non-toxic solution but suffer from issues like Sn²⁺ oxidation, which hampers efficiency and device longevity. They represent a greener alternative but require further development to match lead-based counterparts.

Tandem

Tandem solar cells combine multiple light-absorbing materials to surpass the Shockley–Queisser efficiency limit of single-junction devices. Perovskite–silicon tandems have reached certified efficiencies over 29%.

Progress in tin-based tandem cells could unlock highly efficient and sustainable PV solutions.

Organic

Organic photovoltaics (OPVs) use conjugated polymers or small molecules as light absorbers. They are flexible, lightweight, and suitable for low-intensity or indoor lighting conditions.

Both OPVs and tin perovskites offer flexibility and low-temperature processing, but tin perovskites typically achieve higher efficiencies compared to OPVs. OPVs are non-toxic and stable under indoor use, but degrade quickly outdoors.

Quantum dot

Quantum dots (e.g., PbS, CdSe) are nanocrystals with size-tunable bandgaps, enabling multi-junction or infrared-absorbing solar cells. They are typically used in solution-processable architectures.

While QDSCs offer unique spectral tuning and novel mechanisms (e.g., multiple exciton generation), they generally exhibit lower efficiencies and often use toxic heavy metals. Tin perovskites provide better efficiency and sustainability at this stage, though QDSCs may hold niche advantages in infrared photovoltaics.

Copper-based chalcogenides

These include materials like Cu(In,Ga)Se₂ (CIGS) and Cu₂ZnSnS₄ (CZTS), which are thin-film alternatives with high absorption coefficients and moderate efficiencies.

CIGS cells reach high efficiencies but rely on scarce elements (indium, gallium). CZTS is non-toxic and earth-abundant, but suffers from low efficiencies due to defect-related recombination. Tin perovskites are easier to process, potentially more efficient than CZTS, and could be more scalable if stability issues are addressed.

Dye-sensitised (DSSCs)

DSSCs rely on a photoactive dye to generate current. They are simple to fabricate, low-cost, and function well under low-light or indoor conditions.

While DSSCs are inexpensive and non-toxic, they typically have lower efficiencies and face electrolyte degradation issues. Tin perovskites can exceed DSSC performance in both efficiency and scalability, especially if integrated into flexible devices or indoor-use modules.

Competing ETL materials

Titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide has been one of the earliest ETL materials used in perovskite solar cells, particularly in mesoporous architectures. It has a bandgap of around 3.2 eV (anatase phase) and moderate transparency.

However, its low electron mobility (0.1–1 cm²/V·s) and requirement for high-temperature sintering (typically 450–500 °C) limit its use in modern low-temperature or flexible devices. More critically for tin-based perovskites, TiO₂ exhibits photocatalytic activity under UV light, which can degrade the perovskite layer over time, severely affecting long-term stability.

While it is abundant and inexpensive, TiO₂ is now largely being replaced in tin perovskite devices by SnO₂ and other more stable ETLs.

Zinc oxide

Zinc oxide is another wide-bandgap semiconductor (3.3 eV) with higher electron mobility (~100 cm²/V·s) than TiO₂, and it can be processed at low temperatures using methods like spray pyrolysis.

These attributes make it attractive for flexible solar cells and tandem architectures. However, ZnO has poor chemical compatibility with iodide-based perovskites, especially tin perovskites.

ZnO surfaces can catalyse degradation of the perovskite absorber due to acid-base reactions, and can form interface defects that trap charge carriers. Although surface passivation and interlayer engineering can help mitigate these issues, ZnO is generally not favoured for tin-based perovskites unless specially modified.

MXenes

MXenes are a class of 2D transition metal carbides and nitrides (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tx, Nb₂C) that have gained attention as next-generation ETL materials due to their ultra-high electrical conductivity (~10,000 S/cm) and tuneable surface chemistry.

Their work function can be adjusted by surface functional groups (–O, –F, –OH), enabling customised energy level alignment with perovskite absorbers. MXenes can be deposited from solution using techniques like spin-coating or inkjet printing, making them well-suited for low-temperature and flexible device fabrication.

For tin perovskites, MXenes offer the potential to enhance charge extraction while maintaining chemical compatibility. However, challenges include complex synthesis involving hazardous etchants (e.g., HF), scalability, and stability under ambient conditions. While highly promising, MXenes are still largely in the research phase and require more validation for commercial use.

Key players

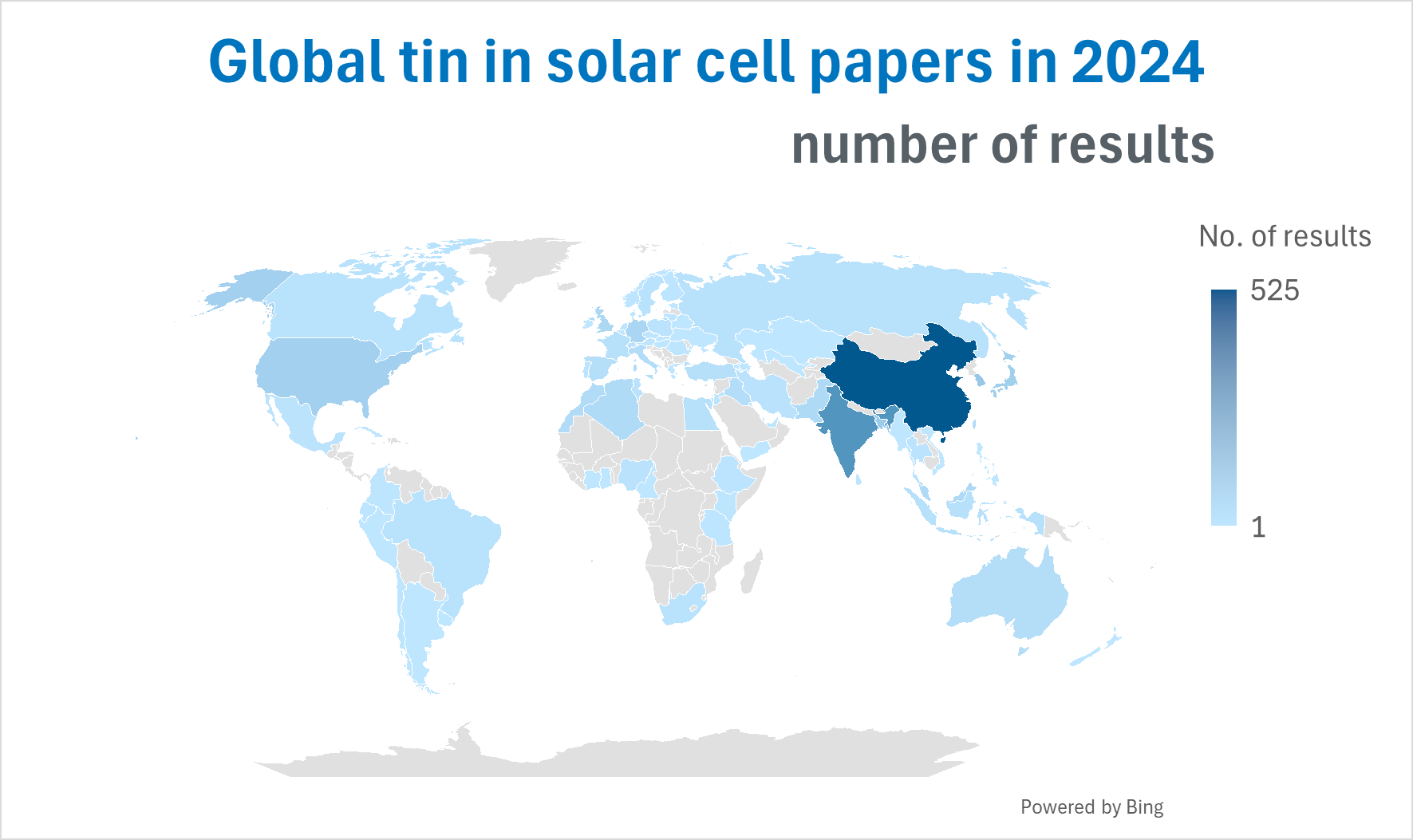

Academic papers regarding the use of tin in solar cells have been on the rise over the past decade, with 1511 papers in 2024 according to Scopus. Of these, 23% of papers originated in China, 13% from India, 6% from Saudi Arabia, and 5% from South Korea. This identifies a dominance of research in Asia.

Academic papers regarding the use of tin in solar cells have been on the rise over the past decade, with 1511 papers in 2024 according to Scopus. Of these, 23% of papers originated in China, 13% from India, 6% from Saudi Arabia, and 5% from South Korea. This identifies a dominance of research in Asia.

Solar panels can and are being used globally. However specific biomes, such as deserts, are ideal for optimal solar output due to long periods of sunlight and dry conditions. It is important to note that whilst solar panels are able to generate electricity, they cannot directly store it, which is why battery systems are essential. Lead-acid, lithium, and emerging sodium-ion batteries can be used to store solar energy. The performance of these batteries is affected by climate similarly to the panels themselves. Extreme highs and lows of temperature can drastically reduce battery performance.

The worlds largest solar panel manufacturing companies are also concentrated in China. China produces 86% of the world’s solar panels each year according to Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems. In comparison Europe and North America each produce 2%.

According to Wood Mackenzie the top 5 solar manufacturing companies in 2024 were Jinko Solar, JA Solar, LONGi Green Energy, Canadian Solar, Trina Solar, DMEGC Solar.15 The majority of these solar companies are producing silicon-based solar cells primarily, but are pivoting to new, more sustainable and cheaper technologies such as tin perovskites.

There are existing solar companies manufacturing high efficiency tin perovskite solar cells. One example is Oxford PV in the United Kingdom. Oxford PV have commercialised perovskite-on-silicon tandem solar cells, which holds an impressive efficiency of 26.8% (certified by Fraunhofer ISE).

This identifies an exciting and rapidly advancing future for tin-based perovskite solar cells.

Future outlook

Tin’s role in solar cell technology is expanding rapidly, driven by its unique material properties, relative abundance, and sustainability credentials. Over the next decade tin-based perovskites could emerge as a major PV technology, especially in lead-free tandem and flexible solar cells. SnO₂ as an ETL material is likely to remain standard in perovskite devices, especially as fabrication methods are optimised.

Tin solder in solar ribbon will remain a consistent use case, particularly as global deployment of PV accelerates. Policy shifts toward non-toxic, low-carbon technologies will favour tin’s use in next-generation PVs.

With coordinated investment in manufacturing scale-up, long-term stability improvements, and recycling strategies, tin could play a critical enabling role in the clean energy transition.

References

- World-leading 27% perovskite cell efficiency record set by UNSW and Soochow University, with ACAP support

- Interactive Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart | Photovoltaic Research | NREL

- https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5c01338

- https://doi.org/10.1002/eem2.12791

- https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202501876

- https://doi.org/10.1021/prechem.4c00107

- https://doi.org/10.1039/D5SE00339C

- https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5c02547

- https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-025-11920-9

- https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15030255

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2025.113595

- https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-024-00260-z

- https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-024-03365-0

- https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8877744

- 2025 solar ranking | Wood Mackenzie